Blessed are the Peacemakers – The Elijah Hicks Story, Part 1.

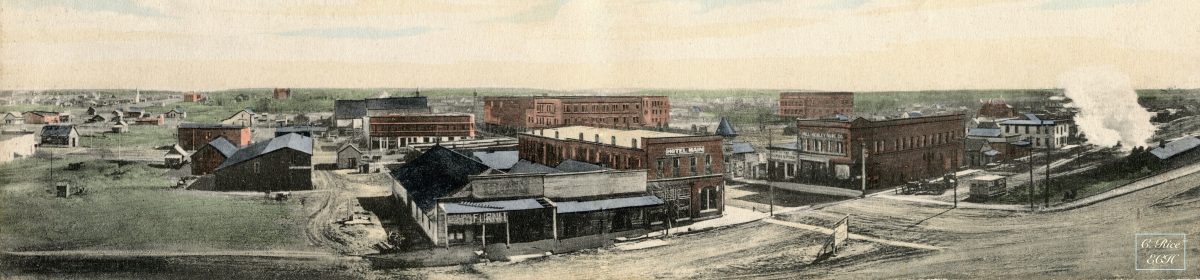

Walking through Claremore’s Woodlawn Cemetery on a peaceful day one comes upon a marker signifying the graveyard’s oldest burial site, the final resting place of one of Claremore’s earliest residents, one who played a significant role in documenting Oklahoma’s history.

This noteworthy Cherokee lived during a time of great Native American transition. Born after the Revolutionary War with the British that gave America its freedom and independence, this Cherokee died before the Civil War that tested independence’s meaning. It was a time of great struggle, of a sovereign nation living within a sovereign nation, each nation grappled to define its existence. Two nations of contrasts, one nation was brand new; the other nation was as old as the hills that established it. One nation was peopled with immigrants; the other nation was peopled with Natives. One nation had great power, authority, and claimed Manifest Destiny as its “obvious fate;” the other nation had minimal influence over its own providence. Each nation had internal struggles. One nation struggled to define who had jurisdiction – federal rights versus states’ rights. The other nation struggled between factions – removal to western lands versus staying in the east in the land of their forefathers and mothers.

Tried in the fires of adversity, these struggles generated brilliant Cherokee Nation leaders such as John Ross, Stand Watie, Sequoyah, Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinott.[i] Elijah Hicks, statesman, diplomat, and peacemaker was one of these whose honorable character strengthened his beloved Cherokee Nation as he served it faithfully for decades. Elijah Hicks survived many such flames in his lifetime. His story, perhaps dimmed in our recollections, is written to resurrect his memory and to highlight his commitment to using his position of authority to bring peace to troubled nations.

Elijah Hicks was born of devout Christian parents, June 21, 1797,[ii] in the Old Cherokee Nation east of the Mississippi River. Elijah was the son of Cherokee Second and Principal Chief (1827) Charles Renautus (“Born Again”) Hicks (1767 – 1827), one of the first Cherokees to be educated in the English style by Moravian missionaries. Elijah was one of eight siblings; his mother, Nancy Anna Felicitas Broom (1803 – 1862), was the daughter of Chief Broom.[iii]

Elijah Hicks married, in 1823, Margaret Ross (1803 – 1862), sister of John Ross, Principal Chief of the Cherokees from 1828 to 1866.[iv] To them were born at least six children – Louisa Jane Hicks Stapler (1825 – 1895, buried Tahlequah); Daniel Ross Hicks (1827 – 1883, buried Tahlequah);[v] Mary A. Hicks McCoy (1829 – 1909, buried Woodlawn Cemetery); Charles Renatus Hicks (1831 – 1870, buried Woodlawn Cemetery); Victoria Susan Hicks Lipe (1833 – 1867, buried Woodlawn Cemetery); Jonathan Ross Hicks (1836 – 1899, buried Woodlawn Cemetery). Each of these grew to adulthood making significant contributions to the Cherokee Nation’s society in his/her own right.

Many well-preserved primary sources remain today to tell of Elijah Hicks’s historical contributions to society. Serving in the Cherokee legislature as clerk of the National Committee and Council, 1822 – 1824, he was responsible for recording the actions of the council’s financial affairs. He signed, along with other leaders, many significant Cherokee documents, written at New Town, with his flourishing signature.

One significant document with twelve articles, a treaty made between the Creeks and the Cherokee, “by commissioners duly authorized by the chiefs of their respective nations, at General Wm. McIntosh’s, on the eleventh day of December, (A.D.) one thousand eight hundred and twenty-one establishing the boundary line between the two nations…” was signed by Elijah Hicks, Clerk N. Council, October 30, 1823. The treaty was also signed and adopted by Jno. Ross, President National Committee, along with other Cherokee leaders.[vi]

Countless resolutions, signed by Clerk Hicks, and others, are recorded in Laws. The Cherokee Nation & C. September 11, 1808, to November 9, 1825.[vii] The underlying aim of these rulings was to organize a unified, civilized, and peaceful nation. An intriguing list of some of these resolutions follows: regarding the salaries of circuit and district judges, keeping of court records, and the pay of district court clerks;[viii] permission for James Brown and Samuel Canda to open and maintain the old road from Lowry’s ferry and set up a toll gate;[ix] and by “seeking the true interest and happiness of their people,” and “fully convinced that no nation of people can prosper and flourish, or become magnanimous in character, the basis of whose laws are not found upon virtue and justice,” a resolution was written forbidding the bringing of “ardent spirits within three miles of the General Council House, or to any of the courthouses within the several Districts during the General Council or the sitting of the courts.” Also forbidden by this resolution was gaming at cards in the Cherokee Nation. The document was signed at “New Town, Cherokee Nation, November 8th, 1822, by order of the National Committee, Jno. Ross, Pres’t. N. Com. Approved – Path Killer (X) his mark. A. McCoy, Clerk of Com. Elijah Hicks, Clerk of Coun’l.”[x] The tremendous vocabulary and archaic language of these resolutions are noteworthy, signifying a superior command of the English language.

The aforementioned resolutions were followed that year and the following by resolutions against willful embezzlement of the sealed letters of others;[xi] the date of superior court sessions;[xii] circuit judges’ authority to nominate “light horse” companies;[xiii] the authority of tax collectors;[xiv] the obligation of private turnpike companies to repair roads;[xv] procedures for submitting private grievances to the council;[xvi] lawsuits regarding debt;[xvii] and the granting of permission to dig for salt outside of half a mile from a salt well belonging to any other person.[xviii] These important issues of the day needed regulating, and the National Committee and Council gave their careful attention to each.

A pause transpired in resolution writing as tension was building within the United States to remove the Cherokee from their eastern homelands. January 19th, 1824, a letter to President James Monroe of the United States, scribed at the “Tenison’s Hotel, City of Washington,” written in a distinctive, well-trained hand, presenting to the President, who was referred to as “Father, the ignorant and wretched condition of your red children.” The letter made request that the federal government intervene on behalf of the Cherokee Nation to stop the escalating pressure to relinquish Cherokee land east of the Mississippi and to halt the illegal intrusion by Georgian citizens upon their native soil. Other grievances were outlined in the letter regarding the unsatisfactory fulfillment of the treaty of Tellico, October 24, 1804, and the negative bias of the existing Indian Agent, Joseph McMinn. This document was signed deftly in ink on sturdy paper by John Ross, George Lowrey, Major Ridge, and Elijah Hicks, each in his own unique scrawl.[xix]

The National Committee and Council went on to address other important matters that reflected the public challenges of their southern, pre-Indian Territory, pre-Civil War, contemporary times. “That no citizen or citizens of the Cherokee nation shall receive in their employment, any citizen or citizens of the United States, or negro slaves belonging to citizens of the United States, without first obtaining a permit agreeably to law, for the person or persons so employed; and any person or persons violating this resolution, upon conviction before any of the district courts, shall pay a fine for every offence at the discretion of the court, not exceeding ten dollars; and the person employed to be removed;”[xx] the opening of a Register’s office to record all advertisements of estray (stray) property;[xxi] commissioning for the cutting and clearing (building) of roads from the Chattahoochee River to May’s, Blythe’s, and Walker’s ferries on the Hiwassee River;[xxii] the forbidding of “disposition and use of ardent spirits” at public gatherings;[xxiii] the duties of marshals, sheriffs, constables, and light horsemen to “bring to justice any transgressors of law;”[xxiv] that free Negroes would not be allowed to reside in Cherokee nation without permit;[xxv] light horsemen would serve as jurors and the judge as foreman in court;[xxvi] forbidding of any non-citizen white person of “bringing spiritous liquors into the Cherokee nation… contrary to law;”[xxvii] the reduction of numbers of light horse companies from six to four and the pay of each rank;[xxviii] restrictions that no person “shall be permitted to settle and make improvements within the distance of one-fourth of a mile of the field or plantation of another, without the consent or approbation of such resident;[xxix]forbidding of setting the woods on fire before the month of March each year;[xxx] responsibility of owner for damages incurred by cattle breaking into the field of another person having a lawful five-feet-high fence;[xxxi] the duty of every light horseman to obey orders of the principal chiefs when called upon to perform any public business for the nation;[xxxii] distribution of monies by the treasurer;[xxxiii] and the appointment for a district organizer and procedure for taking a correct census of the Cherokee nation’s districts by April 15, 1825.[xxxiv] These resolutions, signed by Clerk Elijah Hicks were recorded in detail. Thereafter, starting in 1925, E. Boudinottt signed the resolutions as Clerk N. Council at New Town and then at Echote, 12th November 1825.[xxxv] Many of these laws and regulations were transferred to the Cherokee Nation upon its removal to Indian Territory. Reading and understanding these resolutions explain unique decisions made in future Indian Territory cases before Oklahoma statehood.

From 1826 to 1827, at age 28 – 30, Elijah Hicks was promoted to president of the National Committee of the Cherokee Nation. Beginning with a resolution by the National Committee and Council regarding Isaac H. Harris being appointed as the principal printer for the Cherokee Nation at New Echota, with a salary of $400 per year, Elijah Hicks signed as “Pres’t N. Com.” An editor was to “be appointed whose duty it shall be to edit a weekly newspaper at New Echota, to be entitled, the ‘Cherokee Phoenix,’ and also to translate matter in the Cherokee language for the columns of said paper as well as to translate all public documents which may be submitted for publication, and that the sum of three hundred dollars per annum be allowed said editor and translator for his services. New Echota, Oct 18, 1826. Elijah Hicks, Pres’t N. Com. Major Ridge, Speaker Coun. Approved – William Hicks, Jno. Ross. A. McCoy, Clerk Com. E. Boudinott, Clerk N. Council.”[xxxvi] Amendments to this document continued regarding the Cherokee Phoenix, the cost, and project management of this invaluable publication. Resolutions continue regarding the Unicoi Turnpike company;[xxxvii]suspension of the poll tax and citizen merchants’ law;[xxxviii] indebtedness to the Treasury;[xxxix] and peddlers’ tax reduction.[xl] Thereafter, starting 1828, Lewis Ross signed resolutions as “Pres’t. N. Com.”[xli] Elijah Hicks moved on to other important duties.

It was following this time that Principal Chief John Ross, Elijah Hicks, and other significant leaders intensified legal efforts to convince the US Congress of the injustice of the Indian Removal Act of May 28, 1830.

To read “Blessed Are The Peacemakers – The Elijah Hicks Story,” Part 2, please click here.

by Christa Rice, Claremore History Explorer

Woodlawn Cemetery, Claremore, Oklahoma, Station 4.

Sources:

[i] Elias Boudinott’s surname (also Boudinot) is spelled in several different ways. The choice was made to use the double “t” spelling as this is the way it is spelled in several National Cherokee documents.

[ii] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/8500898/elijah-hicks Accessed: May 13, 2020.

Elijah Hicks Birth 21 Jun 1797 (Emmet Starr suggests the birth date June 20, 1796), Georgia. Death 6 Aug 1856 (aged 59), Claremore, Rogers County, Oklahoma. Burial Woodlawn Cemetery, Claremore, Rogers County, Oklahoma. Memorial ID 8500898.

“Inscription: “Aged 60 years 1 month 16 days. Elijah Hicks was born June 21, 1797, in the old Cherokee Nation East of the Miss. R. Was educated in S. Car. He assumed a high position as a leader in 1832 and 33. Succeeded E.C. Boudinott as Editor of the Cherokee Phoenix in 1838 and 29. Was commander of the Cherokees to their present home. Was one of the framers of the constitution and laws of the Nation. Filled a number of appointments as delegate to Washington City, D.C. to attend to the tribe with U.S. Grant.” Spouse Margaret Ross Hicks.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/29068583/margaret-hicks Accessed: May 13, 2020.

Margaret Ross Hicks. Birth 5 Jul 1803. Death 1862 (aged 58-59), Oklahoma. Burial Ross Cemetery, Park Hill, Cherokee County, Oklahoma. Memorial ID 29068583. Parents Daniel Tanelli Ross. Mary McDonald Ross. Siblings Jennie Ross Coodey (1787 – 1844), Elizabeth Grace Ross (1789-1876), John Ross (1790 – 1866), Susannah Ross Nave (1793 – 1867), Lewis Ross (1796 – 1870), Andrew Tlo-s-ta-ma Ross (1798 – 1840); Maria Ross Mulkey (1806 – 1838). Children Louisa Jane Hicks Stapler (1825 – 1895, Tahlequah). Daniel Ross Hicks (1827 – 1883, Tahlequah). Mary A Hicks McCoy (1829 – 1909, Woodlawn Cemetery). Charles Renatus Hicks (1831 – 1870, Woodlawn Cemetery). Victoria Susan Hicks Lipe (1833 – 1867, Woodlawn Cemetery). Jonathan Ross Hicks (1836 – 1899, Woodlawn Cemetery).

[iii] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/17696080/charles-renatus-hicks Accessed: May 22, 2020.

Chief Charles Renatus Hicks. Birth 23 Dec 1767 (Tomotley near the Hiwassee River). Death 20 Jan 1827 (aged 59) Spring Place, Murray County, Georgia. Burial Moravian Mission Cemetery, Spring Place, Murray County, Georgia. Memorial ID 17696080. Grave Marker reads: “Charles Renatus Hicks, Capt Morgan’s Regt, War of 1812, Dec 23, 1767, Jan 20, 1827, Cherokee Indians.” Spouse Nancy Anna Felicitas Broom. Children Elsie (1760 – 1826), Nathan Wolf (1795), Elijah (1797), Elizabeth (Betsy) (1797), Sarah Elizabeth (1798), Jesse Hicks (1801), Edward, and Leonard Looney (1804). Elijah, married Margaret Ross, half-sister of Chief John Ross. Son, Nathan, married Elsy (Alice) Shorey.

[iv] “Hunter’s Home, The Ross Family”. https://www.okhistory.org/sites/mhgenealogy Accessed: May 20, 2020.

https://www.genealogy.com/ftm/h/i/c/James-R-Hicks-VA/BOOK-0001/0021-0107.html Accessed: May 20, 2020.

The Brainerd Journal, p 348; April 3, 1823.

[v] Daniel Ross Hicks “became a successful farmer and stock raiser. He was influential in political and tribal affairs and for some time acted as United States interpreter. His death occurred in 1883. His wife died in 1866.” Benedict, John D. Muskogee, and Northeastern Oklahoma Including the Counties of Muskogee, McIntosh, Wagoner, Cherokee, Sequoyah, Adair, Delaware, Mayes, Rogers Washington, Nowata, Craig, and Ottawa. Volumes 2. Chicago: The S.J. Clarke Publishing Co. 1922. p. 165.

[vi] https://www.loc.gov/law/help/american-indian-consts/PDF/28014184.pdf Accessed: May 27, 2020. “Laws. The Cherokee Nation, &C.” September 11, 1808, to November 9, 1825. Brooms Town, New Town, & Echota. p. 72-74.

[vii] https://www.loc.gov/law/help/american-indian-consts/PDF/28014184.pdf Accessed: May 27, 2020. “Laws. The Cherokee Nation, &C.” September 11, 1808, to November 9, 1825. Brooms Town, New Town, & Echota.

[viii] Ibid. November 1, 2 & 8, 1822, p. 22, 23 & 26.

[ix] Ibid. November 2, 1822, p. 26.

[x] Ibid. November 8, 1822, p. 27 – 28.

[xi] Ibid. November 10, 1822, p. 28.

[xii] Ibid. November 12, 1822, p. 28-29.

[xiii] Ibid. November 12, 1822, p. 29.

[xiv] Ibid. November 13, 1822, p. 29-30.

[xv] Ibid. November 13, 1822, p. 30.

[xvi] Ibid. October 17, 1823, p. 32.

[xvii] Ibid. November 12, 1824, p. 33.

[xviii] Ibid. November 9, 1824, p. 33-34.

[xix] https://dlg.usg.edu/record/dlg_zlna_tcc035 Accessed: May 21, 2020.

[Letter], 1824 Jan. 19, Washington to James Monroe, President of the United States.

[xx] https://www.loc.gov/law/help/american-indian-consts/PDF/28014184.pdf Accessed: May 27, 2020. “Laws. The Cherokee Nation, &C.” September 11, 1808, to November 9, 1825. Brooms Town, New Town, & Echota. November 13, 1824, p. 34.

[xxi] Ibid. November 12, 1824, p. 34-35.

[xxii] Ibid. October 25, 1824, p. 35-36.

[xxiii] Ibid. January 27, 1824, p. 36.

[xxiv] Ibid. November 11, 1824, p. 37.

[xxv] Ibid. November 11, 1824, p. 38.

[xxvi] Ibid. November 13, 1824, p. 39.

[xxvii] Ibid. November 11, 1824, p. 40.

[xxviii] Ibid. November 12, 1824, p. 40.

[xxix] Ibid. November 12, 1824, p. 41.

[xxx] Ibid. Effective September 1825, p. 41

[xxxi] Ibid. November 12, 1824, p. 42.

[xxxii] Ibid. November 13, 1824, p. 42.

[xxxiii] Ibid. November 13, 1824, p. 42.

[xxxiv] Ibid. November 12, 1824, p. 43-44.

[xxxv] https://www.loc.gov/law/help/american-indian-consts/PDF/28014184.pdf Accessed: May 27, 2020. “Laws. The Cherokee Nation, &C.” September 11, 1808, to November 9, 1825. Brooms Town, New Town, & Echota. p. 64.

[xxxvi] Ibid. October 18, 1826, p. 84 – 85.

[xxxvii] Ibid. October 20, 1827, p. 87.

[xxxviii] Ibid. October 24, 1827, p. 87.

[xxxix] Ibid. October 24, 1827, p. 88.

[xl] Ibid. October 18, 1827, p. 89.

[xli] https://www.loc.gov/law/help/american-indian-consts/PDF/28014183.pdf Accessed: May 27, 2020. “Laws of The Cherokee Nation: Adopted by the Council at Various Periods.” Cherokee Advocate Office: Tahlequah, C.N. 1852.

You must be logged in to post a comment.